*Spoilers Ahead for Black Leopard, Red Wolf and A Song of Ice and Fire*

“I wondered if I would ever stop to think of these years, and I knew I would not, for I would try to find sense, or story, or even a reason for everything, the way I hear them in great stories. Tales about ambition and missions, when we did nothing but try to find a boy, for a reason that turned false, for people who turned false.

Maybe this is how all stories end, the ones with true women and men, true bodies falling into wounding and death, and with real blood spilled. And maybe this is why the great stories are told so different. Because we tell stories to live, and that sort of story needs a purpose, so that sort of story must be a lie. Because at the end of a true story, there is nothing but waste.”

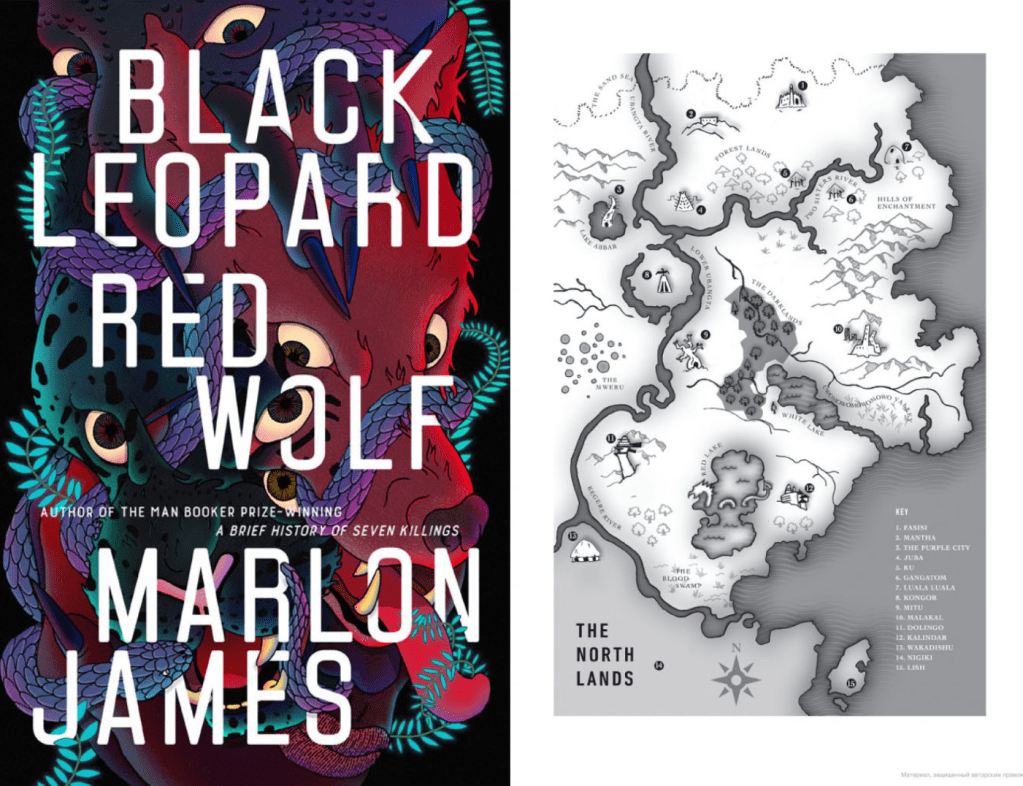

I recently finished Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first entry in Marlon James’ Dark Star trilogy. Having started reading it over a year ago, I can attest that, in my personal experience, the story is not the easiest to consume. Yet, for as long it took me to finish, with multiple lengthy hiatuses in my progress, I think that the story and world James unfurls will stay with me for a long time, and I wanted to dedicate some space here to muse about why.

Welcome to the Real World, Sweetheart

As many (most?) fantasy books do, Black Leopard features a main quest, but the real organizing axis of the novel is the life and perspective of its main character, Tracker. It is said he has a nose. Tracker is a deeply cynical person who nevertheless finds himself experiencing love, caring, and trust even as he suffers for it, time and again. The novel is as much about the turmoil of his heart as it is about the heroes’ pursuit of the missing boy. It is a difficult story to read at times, a vision of a violent world seen through the eyes of a bitter man.

The violence Tracker experiences and inflicts appears, judging from my brief survey of reviews, to be the book’s main feature of interest, and justifiably so. James clearly has thoughts about violence that he uses his fantasy setting to explore. That combination of brutal violence and a fantasy setting has produced the unavoidable comparison between Black Leopard and George R.R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire series, our current cultural reference point for fantasy-but-for-grown-ups, which is to say with sex and gore included alongside the sword fights and sorcerers. James even jokingly referred to his novel as an “African Game of Thrones” during Black Leopard‘s promotional tour (a comment that has haunted him ever since).

I understand this comparison and even made it myself while reflecting on James’ books–and not only because ASOIAF is one of the few other contemporary fantasy series on which I am up to date. Martin’s books are also interested in violence as a theme, in how its many forms become endemic to a world torn apart by the power-hungry.

Still, even for their generic and thematic overlaps, I think it is worth distinguishing how James and Martin are telling quite different kinds of stories. For starters, Martin’s Westeros is primarily seen through the eyes of the powerful, the lords and ladies, the relatively protected whose relationship with violence and danger begins as one of discovery. The Stark children, through whose eyes we are introduced to the Seven Kingdoms, all suffer the experience of having their naivete stripped away in regard to the kinds of people and hierarchies that they have all in some form romanticized.

Tracker and most of James’ other characters hail rather from subaltern positions and, moreover, are identified as some sort of “freak” for various natural and supernatural reasons. They were never afforded the luxury of being naive about the harsher realities of their societies, and are thus psychologically very different from the Stark children or even the more worldly perspective characters whom Martin utilizes later in his books.

These perspectival differences are fundamental to the way that James and Martin talk about violence in their stories and how their depictions land emotionally with the reader. I will be unoriginal to point out that Martin’s series consciously deconstructs familiar tropes from the fantasy genre, mainly those that present the medievalesque fantasy world idealistically (*gestures vaguely in the direction of Camelot*). He draws as much, if not more from the text of medieval European history as he does from the canon of myth and fantasy and has commented that he finds portraying the reality of medieval life more compelling than the “Disney” version. This preference comes through in his series as an internal critique of the fantasy genre. Knights are more commonly bullies than heroes, Martin argues, and pretty maidens will have their dreams of love shattered by the patriarchal institution of marriage. It is only once his characters, Jon, Sansa, Daenerys, and the rest, come to terms with this reality that they can begin to effectively navigate and influence the politics of their world. The idealistic fantasy story is a trap, the claim seems to go, that will render the young heart it ensnares soft and vulnerable to the jagged edges of the real world.

While Martin’s creation has received overwhelmingly positive reception, both generally and specifically for its correction of fantasy tropes, some have criticized him for over-correcting and portraying medieval life not actually more realistically but rather as just a different kind of fantasy, an excessively brutal one. This criticism tends to not only be directed at Martin but towards the “grimdark” subgenre of fantasy more broadly. Shiloh Carroll, drawing precedent works of Umberto Eco and Amy Kaufman, is one such voice who has written frequently on how ASOIAF and, even more egregiously, its more popular television adaptation, Game of Thrones, promote the fetishization of violence, especially towards women, as a token of realism:

“Martin’s darker view of the past isn’t more real. Just because something is edgy doesn’t mean it’s true; […] there was a lot more to the Middle Ages than war, violence, whiteness, and sexism.”

(You can find more of Carroll’s analysis in her published books and articles and on her personal blog)

The notion that ubiquitous violence is a marker of realism is appealing to male writers and consumers–not exclusively but especially–I think, because it clears space within which male characters are invited to act. Men are expected to be the best, most common agents of violence. A few women will be allowed to participate, but they will usually be subject to harassment for their presence in a traditionally masculine space. Hey, it’s just realism.

This does, of course, also mean that the men are the ones more often exposed to serious physical harm or death. Realism. Counterintuitively, however, I would argue that this masculine exposure to harm is rendered as less of an exploration of vulnerability and more as a narrative boon. Those who take the greatest risk are generally considered the greatest heroes, or at least the most brave and interesting. Sure, they may get brutally slaughtered or maimed, but even that can be kind of awesome, no? Death in battle can be spectacular, as much a moving act of heroism as a glorious victory.

In short, the violence men experience in most grimdark fantasies is competitive, an arena for their striving. The violence that women face, on the other hand, is often sexual or domestic, presented as humiliating, restricting rather than enabling their actions, and not so much a consequence of their actions as an inevitability of the world in which they live.

But, hey, the defenders of the grimdark style will doubtless object, that’s just realistic. Whether this claim of realism is true or not, we may disagree. But I would argue that, even if we accept that this kind of violence is a form of realism, it is at least ALSO a macho, patriarchal fantasy for some, possibly many.

“I think people are used to violence, but they’re not used to suffering.”

—Marlon James

I don’t wish to come down too harshly on George R.R. Martin’s writing. Leaving arguments over realism aside, his work uses its critique of traditional fantasy not just for its own sake but to comment on class and power in ways that I find compelling (about his takes on gender, I am slightly more tepid).

Yet, I appreciate James’s writing and worldbuilding for how it handles violence differently than Martin’s. There is no sense here of violence being used didactically as a cure for naivete, be it the characters’ or the readers’. Black Leopard does not feel burdened by the need to reproduce a more historically accurate fictional landscape, nor is it uninterested in the realities of violence, but the specific realities it plumbs are more often emotional than political.

As discussed above, Black Leopard is a more intimate story than Martin’s Song, and not merely because it keeps to the perspective of a single character. Tracker is our only point of view, true, but we the reader are also positioned as if in conversation with him. Tracker narrates his tale to an “Inquisitor,” whose enigmatic person we must uncomfortably inhabit while we listen. We stand implicated in this man’s suffering. We are holding him captive, forcing him to reveal the life he lead that brought him to us in this dungeon.

And what a life that has been. Black Leopard also portrays a much more fantastical fantasy world, brimming with magical people, shapeshifters, and creature monsters. In fact, the book reminded me of nothing so much as Ovid’s Metamorphoses, featuring a new strange event or being at every turn, up into the last few pages. It is an imaginative creation that does not cling too tightly to realism. This is not to say that the events of the book seem abstract. No, the world and characters and actions are all realized very vividly, often uncomfortably so. Cannibals and vampires and night demons all rend human flesh with ease. Conversely, the mingi children born with unusual shapes and abilities, monsters of a different sort, are killed or shunned by human society. In this way, the bizarre world of Black Leopard remains grounded and familiar. Flying bat-men there may be, but the vulnerability of the human body and the capacity of human culture for cruelty remains constant. I think I have been here before.

Yet at no point in Black Leopard did I feel as though I were being instructed in how “the real world works.” In part, this is a product of Black Leopard‘s specific genre bent. It is, as we have noted, a fantasy that embraces many of the more outlandish bents of the genre. I say again, flying bat-men. Yikes. Mostly, though, the different impact of Black Leopard‘s violence is a product of the intimacy between narrator and reader, with no third person to push us into a more comfortable distance from what happens to Tracker and the impact that it has on him. The things that happen in this fiction world are not important or engaging because they offer a persuasive imitation of reality but because they happen to Tracker. He, the man, with all his foibles and carefully cultivated bitterness is plenty real and not in a way that is easily constructed as flattering to the reader.

Likewise, because of that unfiltered closeness between us and Tracker, we are not obliged to accept his perspective on any matter as ultimately authoritative. It is not always clear that Tracker is being completely honest with us. Even in those moments where it seems that he is, especially in the final moments of the book as he embraces despair and declares the meaninglessness of the story he has told us, what matters is not that we believe that he is right but that we understand him. And I felt like I did.

What is Fantasy For?

This blog post proved difficult for me to finish, partly because I am lazy but also because I feel I have struggled to say here everything I think. The more I have thought about the fantasy genre and what authors like Martin and James are doing with it, the more I found myself wanting to hedge my statements with several “buts” and “ands.” I don’t think I have succeeded in grasping or communicating what I think about fantasy violence, but, nonetheless, I am kicking this post out the door. I had to do it eventually. My whole two readers were going to miss me (Hello, C and Y!).

I did, however, want to append one final thought.

In the time since I began writing this post, I started and finished Ursula K. Le Guin’s Tehanu, the fourth entry in her Earthsea series and another fantasy novel of a very different tone and scope than the two series we have been discussing. The Earthsea books are or have become in the course of the vicissitudes of genre much more standard fantasy fare, full of wise wizards, heroic princes, and supernatural evils defeated by the ascension of the One True King.

Le Guin, though, folks will know was not exactly a monarchist. How then can we account for her writing the character Lebannen, the goodly young prince who becomes the perfect king? The obvious answer that presents itself is that we should probably not take the story so damn literally, that Lebannen is not an argument for monarchy but first an exploration of a boy’s growing up and then a portrait of a good man who dispenses with what power he has responsibly and kindly. If someone must be king, then it ought to be someone like him.

The counter to this course of thinking is then to ask why the metaphor of kingship is so appealing and if leaning on the imagery of royalty implicitly undergirds actual monarchies by depicting them in a romantic light.

The answer, of course, is that both are true, but I think that we as a culture have sidled a little too far into the latter camp. We have, it feels like, lost some confidence in our own genre savvy to know that, no, kings are not literally a good idea and that dragons as a species are so unlikely. Six limbs?! No real species of reptile have that many! Favoring the aesthetic of realism can be a balm to this doubt that we may be politically or emotionally naive. But if we don’t give ourselves the leeway to enjoy stories that grasp beyond the literal or historicizing, we’ll miss out on some real gems, Tehanu among them, that tell stories not just of kings and wizards but farmers’ wives who grapple with being ordinary women in a realm that prizes male prerogatives and masculine power.

Anyway, if I’m right and we are experiencing a bought of genre anxiety, then the solution is simple: let’s all read more fantasy!